Utena - introduction

I just watched Revolutionary Girl Utena and—what the what?

This introduction is for people who want a little basic orientation to the Utena strangeness that bombarded them. It’s what most people want, and rightly so. Reading the rest of my analysis takes longer than watching the show, and tells you less! Read it if you want, though. I sure won’t stop you.

Utena is an overwhelmingly large smorgasbord, and what you take from it (especially at first) depends on what stands out to you. People have very different takes. They choose different dishes from the table, and it’s because they have to. You can’t take in everything at once, it’s humanly impossible. More—no one person understands everything in Utena, and nobody ever has, including its creators. Here are a few dishes that you might start with.

The hero. Utena (the character) is in many ways a conventional anime hero. She is earnest, self-sacrificing, and not too bright. She follows in many ways a conventional heroic story arc: She meets adversity, wins triumphs along the way as she advances and becomes stronger, and faces a threatening final showdown. If you watch a lot of anime, you can probably name several heroes who fit the description. In the end, she fails her self-proclaimed goal of rescuing Anthy, but she does not fail her true test. She transcends her role as hero.

The abused. Anthy is an abused woman, and not at all a conventional anime character. She is trapped in an abusive relationship—of a complicated realistic type that real women can be trapped in—and does not believe that she can or should leave it. Akio captured her emotionally and intellectually, and keeps her under his control. He usually trusts her and allows her a long leash, but when she disobeys he turns to psychological abuse or physical violence. In the end, inspired by Utena, she changes her mind and leaves to seek Utena. It’s fair to read Utena as first and foremost about abusive relationships and how difficult they can be to escape. Anthy needed the help of an idealized and overpowered storybook hero, and it was barely enough. And, a key point, she must make the decision to leave by herself; nobody can rescue her. That’s realistic too.

Anthy is an extraordinarily subtle character. She is mysterious and hard to read, and her personality has layers. There is way more going on with her than you are likely to realize after watching the show once or a few times. But it is possible to learn her tells and tease out her interior world.

It’s a gay, gay world. “Heteronormative” is not a strong enough term. Akio brought about a society that enforces compulsory heterosexuality (Wikipedia). No matter what your inner feelings may be, you must act as though you are straight and you must follow a socially-accepted conventional sex role. That’s why Juri cannot admit that she loves Shiori, even in private to Shiori. Utena does not realize that she loves Anthy until episode 37, near the end of the series. The idea is not available to her; she lives in a culture that suppresses it.

At the same time, Utena shows us over and over, through obvious events and little details, that hardly any character actually is straight or enjoys their conventional role. Saionji and Touga end up together. Miki appears asexual (though not aromantic). Sneaky clues say that Nanami loves her enemy Anthy. Boys at the bulletin board put their hands on each other. Even the vice principal is hinted to have the hots for Akio (as well as his more visible attempt to corner Juri in episode 7). Tatsuya (Wakaba’s onion prince) appears to be straight. But he’s not happy. Akio himself freely breaks the rules he enforces for others, and sometimes controls people by inducing them to break his rules.

All Utena characters are messed up. They are forced into unnatural roles, how could they be well-adjusted? Utena is a story of dysfunctional cultural prescriptions and how Utena and Anthy at last triumph over them. It’s a particularly tasty dish on the table.

This not what J.B.S. Haldane meant in 1927 when he wrote “The universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.” But it kinda fits.

mystery symbols

Utena flaunts its strangeness. It loves to drop in jarring surreal bits that are plainly symbolic and... sometimes hard to figure out. Especially as it gets closer to the finish. Explaining a few may give a flavor, though there is hardly an end to them.

Three candles. In episode 30, three metaphorical candles follow Utena around. Real candles don’t move around on their own, and if they burn all day they burn down. Utena blows them out one by one, and what the begonia is that about? It stumped me for quite a while.

The cake is not a birthday cake, but the candles are birthday candles. When Utena has blown them all out, she will be granted her birthday wish. She wants to violate her own ideals to be with corrupt Akio—she wishes to be corrupt. In Utena, light is for moral goodness, and darkness is for evil. When the candles no longer give light, she has chosen to become corrupt. When she blows out the last candle, she lies to herself. It is her first deliberate falsehood in the series. The candles tell us how Utena sees herself—they show what, in the moment, she most wishes for.

Playing a role. It’s the next episode, and Utena is corrupt. And she’s jealous of Nanami seeming close to Akio, and in general does not have a sound understanding of the situation. She wants to hide her corruption and her jealousy, and she especially wants to hide them from Anthy who she cares about. She is Akio’s sister, after all. Utena tells a joke to cover up her feelings, but her telling is clumsy and she holds her hands behind her head, showing embarrassment. Utena has been honest and open her whole life, and her deception skills are zero. Anthy understands at once and teases Utena in a way that reveals the truth.

And the unexpected movie camera? Utena is lying, but she is playing the role of an honest person. She is, metaphorically, acting in a movie. Anthy illuminates the truth: She holds up a white card to reflect fill light into the movie scene. The movie camera tells us how Utena sees herself, and the white card tells us how Anthy sees her role.

Touga’s carrot. Utena is absolutely saturated with sexual symbols. Touga’s phallic carrot is my favorite.

In episode 35, Touga gives Utena earrings, lying as instructed that they are from Akio. It makes no sense—Utena and Akio live together in the tower so why send an intermediary—but Utena can’t tell. He brings a carrot for no reason and plays with it the whole time, and nobody notices or cares. That means it is metaphorical: He lusts after Utena. In this picture, he holds it to his head as if he were a unicorn and it were his horn. He does not know that Utena and Akio had sex in episode 33; he believes Utena is a virgin. A unicorn’s horn has magical purifying power. He wants to, as it were, touch Utena with his horn and purify her from feelings for toxic Akio. The carrot tells us how Touga sees himself. He is that stuck up, and that toxic himself.

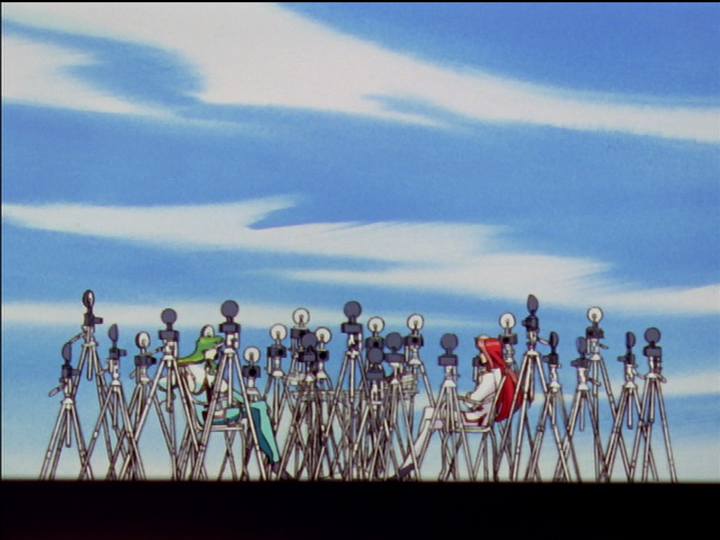

Reporters. Touga loves Utena, and Saionji loves Anthy. But so what? They are in a gay relationship with each other. Some viewers don’t even notice, depending on their background, but to others it is undeniable. In this picture, they are surrounded by news cameras flashing. In another, they are surrounded by news microphones listening in.

Why is the news media here? In Utena’s world of compulsory heterosexuality, their relationship is not merely frowned on. It is scandalous. The media is not really here; Touga and Saionji are alone. But they know they are doing something scandalous, and they imagine the news blazing out into the world. Like the other symbols, the cameras tell us about how the characters see themselves at the moment.

it’s an allegory

Switchup: The series is no longer a smorgasbord, now it is a three-course dinner with each flavor fine-tuned to enhance the next. It gets a bit detailed, but this is how I understand it:

Revolutionary Girl Utena is an allegory of the sexist patriarchy. Akio is the personification of the patriarchy; he sets the rules and controls society. Anthy is effectively his slave, and he has lesser control over everybody else. Anthy personifies all women who believe in the patriarchy, and Utena is those who seek to defy it; together they are all women. Anthy and Utena are complementary and fit together like puzzle pieces: Each one’s strength or trait is the other’s weakness or opposite trait. Both must leave Akio to overcome him; he cannot be defeated by a few people like Utena who opt out. To succeed, Anthy and Utena must love each other. A woman must love herself, and disbelieve the patriarchal lie that she is inferior.

Dios is the central character of the allegory. He is the prince, a fairy tale hero who can win through against all odds and accomplish miracles. He aims to rescue all girls and “kiss” them. Dios is a figure from children’s stories, made up to teach children their patriarchal sex roles: All boys are to seek to become powerful princes, and girls are to seek their princes to submit to. He personifies the false cultural narratives of the patriarchy. Anthy and Utena love Dios, at first.

In the story, Akio seeks the Power of Dios so that he can accomplish miracles and have absolute power. In the allegory, it means that he seeks total control over cultural narratives so that people will believe anything he wants, granting the patriarchy absolute power and eternal changelessness. The Power of Dios is the power of stories—more strictly, the power of stories that are believed. The Power of Dios can accomplish miracles because stories can convince people to believe the impossible. Utena symbolizes false beliefs as illusions, and shows that miracles are illusions.

Akio victimizes many children over time, cruelly manipulating them in hope that they will develop the power he craves. If one does, he plans to steal the power and murder them. All the Student Council members are his victims, and there are others. Finally one of his victims does start to develop the power of miracles. It is Utena, and Revolutionary Girl Utena tells her story, which is the same thing as her power. Utena is self-referential!

One way to look at it is that the anime Revolutionary Girl Utena is Utena after she has disappeared from Ohtori Academy and appeared in the real world. She is here on Earth, still working to defeat Akio with her power of stories.

Allegories are made of symbols by nature. In Utena, virtually everything is symbolic: Events, personalities, character designs, names, costumes, colors, light and shadow, architecture, flowers, animals, the city, the ocean, the background greenery and blue sky.... You can love the show without ever reading the metaphors layered into each frame, but if you do make the effort you will be surprised by some of what you find out. I sure was. There are hard-to-notice references to fairy tales, Greek myths, Buddhism, and Christianity, not to mention fine art, anime, obscure movies, and many other sources... and I promise with certainty that there are many references I don’t know about. Utena is endlessly detailed.

the story arcs

There are a lot of characters in Utena, and each one illuminates the central themes differently. And there are a lot of events along the way, including 21 duels. But Akio (often through Anthy) directs major events, even before we meet him.

There are no filler episodes. Everything counts. Touga boxes a kangaroo, and it tells us about his plan to defeat Utena. Nanami turns into a cow, and it is central to the symbolism. Nanami finds an egg, and it makes more cogent points than I can list (though I try). The fluffiest episode, in my opinion, is the recap episode 24 with Mitsuru, and it too makes serious points that should not be missed.

The prince story is shown as a children’s cartoon at the start of episode 1 and repeated in other episodes, and told in greater detail later on. Akio selects Utena as one of his child victims. He likely murders her parents to make her susceptible to his tricks. He pretends he is Dios, and fools little girl Utena into wanting to be a prince (so that she may potentially develop the Power of Dios) and into wanting to marry the prince (so that he can control her). Utena does not notice any contradiction in her aims, even years later.

The Student Council arc. It’s not obvious, but Anthy manipulates Utena into joining the duels. Utena remains trapped in the dueling system until the final episode. In this arc, Akio tests Utena to see whether she has a nascent Power of Dios. The arc boss Touga is his final test. So far so good!

The Black Rose arc. There are two threads of events. In one, long ago, Akio had Mikage and 100 special boys research the dueling arena, so Akio could understand how it works. (It is not Akio’s creation, it is part of Utena’s natural world.) In the other, at the current story time, he trains Utena’s power. It has to reach full strength before it is worth stealing. The dueling arena is arrayed with classroom desks; it is miracle school. In most duels, Utena starts behind the desks, in the student position, and faces a teacher who attacks. The two threads happen at distant times, and yet they overlap. Time is confused in Utena.

The Apocalypse Saga. Akio continues efforts to increase Utena’s power, but his primary focus shifts to keeping Utena under his thumb. Her power is worth stealing only if it is greater than his, and that makes her a risk. He systematically lures her step by step into a sexual relationship. By episode 36 she is fully in love with him and deeply corrupt. He even tempts her to cheat on him, and she does without a thought. Things become uncertain in episode 37, but she chooses to wear her ring and meet him in the arena. Utena wants to wear the prince’s ring so she can rescue Anthy. Akio wants Utena to wear the engagement ring so he can marry her: In his world, the husband controls the wife. Utena refuses to marry him, and there is a complicated final showdown before Utena and Anthy, separately, leave.

Utena is shanghaied into the dueling system, shanghaied into a self-improvement class, shanghaied into a hotel, and finally escapes.